Looking backWhen watching the sky during a sunset, most people tend to look sunward. After all, that is where the action is, where clouds glow when the sun illuminates them from behind and where the most spectacular color display is.Yet, occasionally it can be also worth turning one's back to the sun. What can we see then? If there are no clouds, there usually are no spectacular colors to be seen. But the sky doesn't just gradually get darker - rather there is an orange-violet tinted smudge at the horizon which grows higher and higher as the sun continues to sink - the Belt of Venus. If there are clouds in the sky, they are illuminated quite differently from sunward clouds - the light hits them from the front, and dependent on cloud type and optical thickness, this can produce rather unexpected visuals. Especially high towering Cumulonimbus clouds can look very spectacular when seen away from the setting sun when there is a color gradient from the brightly lit cloud tops to the cloud base that is already in shadow.

The Belt of VenusWhat is the Belt of Venus? In clear air, it shows rather prominently as a band on the horizon.

In essence, it is nothing but the shadow of Earth cast into the atmosphere. Since the surface of Earth is curved, the region behind a sunward-looking observer is progressively 'falling away' from the light rays, and hence no longer directly illuminated. As a result, the blue Rayleigh glow ceases and the atmosphere darkens.

Why is it not completely dark? That has to do with multiple scattering - photons can be scattered downwards from the lit upper atmosphere and give rise to a residual Rayleigh glow there - providing an indirect illumination for the lower atmosphere. As time passes and the sun sinks more and more below the horizon, the Belt of Venus grows higher and higher above the horizon, but eventually loses its clear definition and becomes blurred, ultimately to end up as a darkening sky above the observer.

Cloud illumination and dark-liningWhen turning away from the Sun, any visible clouds have illumination full in front. That means they're brightly lit, doesn't it?Not necessarily - look at the following daylight example of clouds being directly illuminated (really):

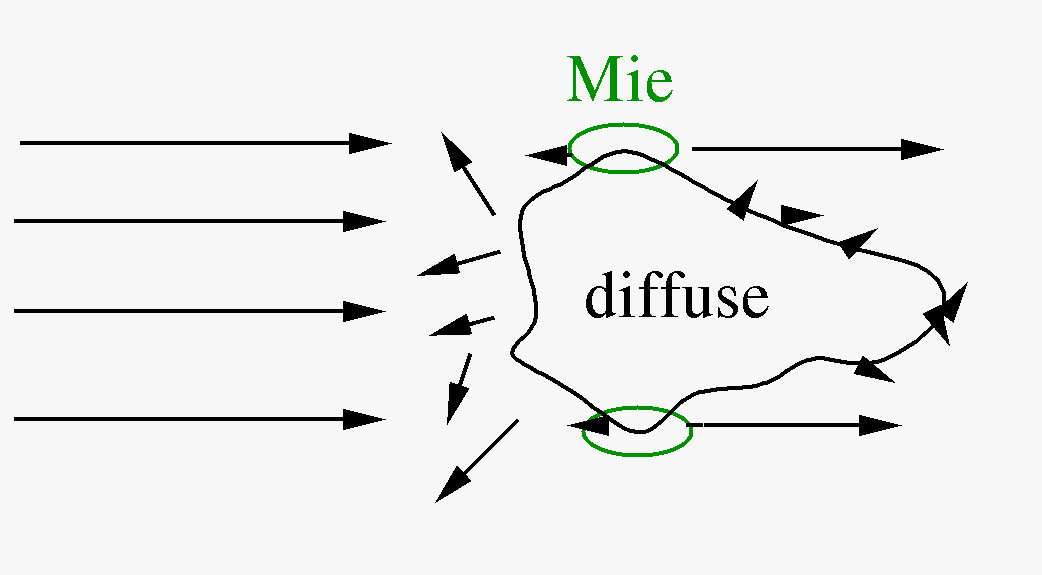

They look dark. Are they in shadow? The fact that the faint fringes and filaments look darkest suggests yet another explanation - Mie scattering. We've previously seen that light falling onto thin clouds is predominantly scattered forward, giving rise to the bright glow of silver lining. Now, of course that means if the light is going predominantly forward, it isn't scattered back. So the silver lining seen from the other side appears as a dark fringe around the cloud body.

Is is Mie scattering seen from the other side which makes clouds in direct light appear dark - if they're translucent enough. If they start to be opaque, diffuse scattering takes over and the cloud behaves as we are used from solid objects - the illuminated side is bright, the shadowed side is dark. Otherwise, many of the processes discussed earlier also apply to the away-side. For instance, the following picture shows a high haze layer already illuminated by the rising sun, whereas a lower layer is still in indirect light only and takes a blue-violet color. Since the indirect illumination is chiefly from above, there is no dark-lining visible yet - this appears later when also the lower layer is directly illuminated.

Continue with Icy hazes. Back to main index Back to science Back to sunsets Created by Thorsten Renk 2022 - see the disclaimer, privacy statement and contact information. |